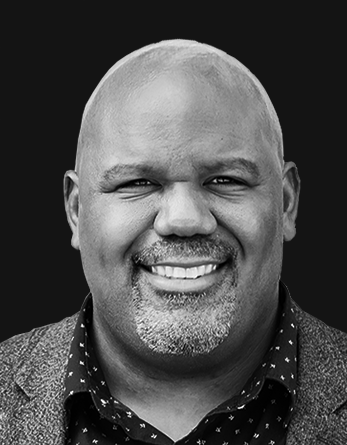

An interview with Jerome Gay Jr. and James Roberson

Racism is the oppression of a group of people for the preservation of another group of people. Whether systemic or subtle, racism robs its victims of security, dignity, worth.

Either a pastor’s response will help those affected to wade through the resulting feelings of anger and frustration in a God-honoring way, or it will leave them discouraged, defeated, and wondering how to navigate the offense.

Caring for a victim of racism can be difficult whether the pastor has experienced the sting of ill treatment because of skin color or not. That difficulty is compounded when the pastor is a different race from the one seeking help.

But take heart. There are ways every pastor, regardless of race, can care for victims of racism. James Roberson, lead pastor at The Bridge Church in Brooklyn, NY, and Jerome Gay Jr., lead pastor at Vision Church in Raleigh, NC, both African American, agreed to share how they have helped those who’ve experienced racism.

What are some of the frustrations your people share with you regarding racial injustice?

Jerome: There are a few things I keep hearing over and over again: racial profiling / police brutality, systemic mishandling and injustice, and silence from white Christians.

And I understand. I’ve been profiled—even when I’m not wearing a hoodie or baggy jeans, which has become synonymous for “thug gear.” Oftentimes I hear from those who’ve experienced this too, and they say their white Christian friends respond as if they’re making it all up.

James: Because the stench of racism is everywhere on the news and social media, it captures the atmosphere and brings up the pain of past hurts and gets people talking about past offenses.

How have you helped them deal with their anger?

James: My first step is to unearth the hurt. We do that by asking questions and listening. What happened? How does that make you feel? I call it “cultural learning.” This may be difficult for the majority culture pastor because they rarely have to be in the position of a cultural learner, but it’s one of the greatest things pastors in the majority culture can do. Hear the hurts. Listen to the pain. Know going into the conversation that one’s seminary training probably hasn’t offered practical insights for the moment.

Often, there is work to do beyond listening. There is a corrective element about helping people process through their pain. But, that’s not our first step. Our first step is not, “Get over it.” Our first step is to listen.

Jerome: I agree. I’ve found if you give someone your ear, then they’ll want your voice. So before you speak, just listen to what the person has to say.

Beyond that, we work to move them toward forgiveness. However, I think sometimes we as Christians can go too quickly to forgiveness. It’s good to remember that even in the context of salvation there is repentance, meaning an acknowledgment and turning from sin. We don’t want to send a message that it’s okay [for the offender] to ignore the injustice the person may have encountered.

We have a great example of this in Acts 16:35–39. Paul was beaten by the police and taken to the magistrates. The text says when they realized he had dual citizenship and he was in fact a Roman citizen, they wanted to silently free him. But Paul said (paraphrasing), No. You guys beat me publicly, and I want a public apology. Paul, as a victim of police brutality, demanded they acknowledge the wrong they’d done. It’s interesting for me to see this account in Scripture and know that what we’re seeing across the country and in the media is something we need to pay attention to and address … that we can’t and we shouldn’t ignore it.

How do you help people who feel they’ve experienced racism but really haven’t?

James: This is valid because sometimes people will have anger over perceived racism when there may be a real issue with, say, personal responsibility. But it will likely do me no good to say, “Hey that’s not racism, that’s …” What I must do is help him see what personal responsibility looks like. We may have to have a hard conversation about irresponsibility or laziness, but we can’t just assume those are the problems. The key is not to say, “Well, you’re wrong.” You still have a person who needs to be empowered. Here again is a perfect place to ask questions. Why do you feel it was racism? Have you or anyone close to you been discriminated against in the past? You may discover a history of real victimization, or you may find they have an incorrect definition of racism.

Has dealing with racism opened doors for you to share the gospel / do outreach?

Jerome: I’ve found that as I dig deeper in reading and learning about social justice issues like this, more opportunities open for me to share the gospel with nonbelievers. Discussing it on social media has opened doors for me to have one-on-one conversations. Guys will even message me to discuss aspects of race and faith. And next month I’ll be speaking at a conference on the subject. I’m preaching it from the pulpit, counseling, and providing forums for honest dialogue about the issues.

How can pastors be more sensitive to those dealing with racism?

Jerome: There are a lot of ways pastors can be more sensitive to those dealing with racism. Here are a few:

1. Affirm that these are real issues and it’s something that shouldn’t be ignored. I think black people by and large feel ignored when it comes to issues like this. And in some sense we feel abandoned by white evangelicals when the gospel seems to be used as a scapegoat rather than a refuge.

2. Engage with people of other cultures and work to understand the plight of people different from you. When you do, what’s likely to happen is that you’ll gain more empathy, you’ll gain more sympathy, and you’ll want to join them in the struggle they’re facing.

3. Seek to become students and not be paternalistic. If you’re coming from the majority culture, it’s hard to see the plight of others because you view the world from your own place and position of privilege. Since you can never know what it’s like to be them, you can’t assume that everything you think about them is correct. When you put yourself in the position of a learner as opposed to a teacher, this will help you as you seek to serve those who’ve been hurt by racism.

James: That’s a good list. I would add self-correction. You wouldn’t burst into a hospital room as a healthy, able-bodied person, who’s only ever hurt your finger one day or maybe broken an ankle, and glibly tell a cancer patient to just pray it away or trust God.

In the same way, if you’ve never been a victim of racism, or police harassment, and your thought when sitting with someone who has is, If you just obey the law and the commands of the police, then you’ll be okay, or, you begin to share about how God has placed all men under authority and you start teaching folks about the structure of the government in God’s economy—you need to stop and self-correct.

A wise friend, a wise pastor, wouldn’t immediately jump into a conversation about racism with a theological correction to share. There will be times to talk about trusting God through oppression and injustice, and that vengeance is His. However, a wise friend would sit with folks and have a ministry of care by being present with them in their pain. A caring pastor would take the posture, “I care for them, so I care that this hurts them.”